|

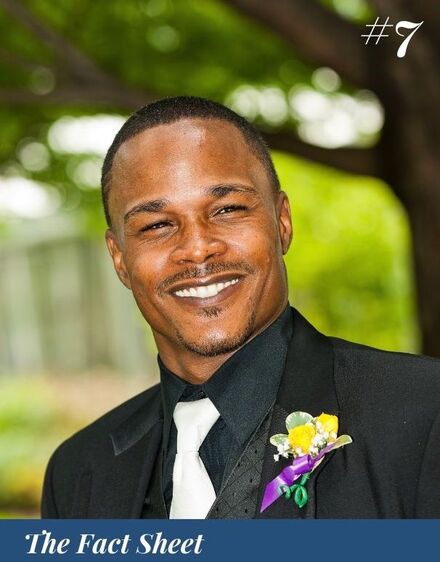

LaVonte Stewart is the founder of Lost Boyz Inc., which decreases violence, improves social and emotional conditions, and provides financial opportunities for the youth in Chicago’s South Shore community. With baseball training and competitive participation as core drivers, Lost Boyz achieves its mission through high-intensity mentoring, intervention, and social entrepreneurship activities.

LaVonte started Lost Boyz after serving four years in a Missouri prison on a gun charge. The organization has evolved to include an array of services for boys and girls in South Shore. LaVonte's also spent many years working in state government. He completed his bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree at Chicago State and also possesses a Master of Public Administration from DePaul University. And now, just the facts! BD: Going back to the purpose of The Fact Sheet, I’m really curious about how people make the choices they make about their lives and their careers. There are a lot of ways people could invest in the youth of South Shore, but you chose to do it through a pretty unique means. I’m curious how you made that decision. LS: It was kind of a confluence of my life experiences as a youth, as an adolescent and the troubles I ran into as a young adult. I was incarcerated from roughly the age of 20 to close to 25. I came home from prison from Missouri, where I was attending college in a small town halfway between Kansas City and St. Louis. I was there on a double athletic scholarship, on baseball and football. I had been academically dismissed from an HBCU, Hampton University, where I had been part of an amazing football program. I really got off track a bit, from the glamour that came with being on the football team. There was this toxicity that I believe particularly black males take from Chicago. It’s very authentic: you know a Chicago person when you see a Chicago person. You can really distinguish the true Chicagoan, especially a South Sider or West Sider. There is this toxic masculinity that I think ties back to gang culture and street culture. It impacted your life growing up on the South Side no matter what community you’re from. Given that, I came home after making that mistake in Missouri. I had a lot to think about during that four years in the Missouri Department of Corrections, and I knew I didn’t belong in that place for a number of reasons. I was very productive there, and I did a lot there. I helped to create a major program that went across the Department of Corrections in Missouri called Therapeutic Communities, a model utilized in prison systems to deter violence and encourage personal development and personal responsibility. BD: I can’t imagine how difficult the transition must have been for you after being in prison. LS: I was really focused on working and getting some money in my pocket. I couldn’t just rely heavily on my parents. I returned to school at Chicago State. It wasn’t a bad option; it was affordable, sort of like an HBCU and it was easy to reach. My mom had gone there. But I struggled a lot. I became a boisterous advocate for ex-offenders. Once you get that label on your back, it is really tough. I knew that I had a certain degree of intelligence that would be a tremendous asset in the future. And none of that mattered any more. Even with degree attainment, with potential employers all bets are off. Now things are improving for that segment, with a lot of talk of criminal justice reform. I landed a few jobs and was laid off. The struggle was real. Fast forward a few years, and I found a flyer in the neighborhood. This guy had recreated my childhood Little League, South Shore Little League, which had been defunct for about 20 years. There was this nostalgia, and I wanted to be involved again. I loved sports, and my sporting career ended prematurely because of the mistakes I made. Baseball was the first sport my mom put me in so it was naturally a first love. I reached out from the flyer and joined as a volunteer coach. I first coached an 11- and 12-year-old team and we won the league championship. I was kind of hooked right then, first year in. I kind of took a ragtag team they just gave me, and not with a lot of experience, and I worked hard and those kids worked hard. So I was hooked. I coached for a couple of years until one day the coach decided to fold the league. And I’ll never forget I was in practice and I had to break the news to the 12 kids playing for me that this league is going to end. This team is going to end. I said I would help them find a team, if they were interested. And at the moment I was making that announcement, an incident occurred. A very traumatic incident. It was the middle of the afternoon in summer time, and I see two assailants chasing another guy across the park. And this was at a time when our park was pretty bad. The park had a notorious reputation and a lot of trouble went on in the park. I’m old school so I hit the dirt, and I noticed that the kids didn’t. They were standing around laughing, watching, talking. I had an epiphany that this generation of children is so desensitized to violence that this has become normalized. This is considered just regular behavior. It should have been fight or flight, and not this third option of apathy. My brain got to spinning. First there was this sense of guilt because I thought about some of the things that I had done in the community as a teenager, things my parents would not have been proud of about me. And just thinking through, how did I get here in the first place? I came from an upper middle class family, two parents. It was the American dream. So how did I get sucked into this side of violence and street life and drugs? It dawned on me that a lot of this was due to negative peer pressure, trying to assimilate with those around me. I stood out because of my unique economic condition. There was jealousy from peers. So as a child you’re not able to process that jealousy so you just want to fit in, like any kid. So thinking about all of that was the impetus to start Lost Boyz. BD: What about the name, because some people might say it comes across in a negative way. And in fact, you serve quite a few girls now. LS: It was thinking about the stakeholders and supports in my community growing up, and there weren’t a lot. There was not as much as there should have been for young people: mentors, engaging youth, or someone just being there for kids. At that point, I said, “these boys are lost. They’re lost boys.” Not because it was an indictment on the kids themselves, but you have to look at the community at-large because I truly believe in that village approach to social growth and development, that there have to be a number of touch points in terms of who’s involved with the child, their decision making. It’s not just the parents, it’s the schools, churches, youth organizations. With all of that in mind, that is where Lost Boyz the name came from. It was an indictment on the adults in the community. If you look at the definition of the word “lost,” it’s where someone relinquishes control over or supervisory obligation over. I was saying adults dropped the ball in my generation and now we’re dropping the ball with this generation. That’s how the name came up. It also had some shock value to it—and truth to it. It’s not a negative name, it’s the reality and it's designed to grab your attention. BD: What was next after the league folded? LS: At that point I didn’t want to let the kids go, so it became a barnstorming club. I started finding teams in other leagues to see if they would give us games. I went to local stores to see if they would donate money or items, and I was able to gather up pants and a little bit of equipment. I was then in the process of making it a legitimate nonprofit. I knew that to solicit donations, I needed to become a 501c3. That became a path, to seek the tax status to receive donations. It ultimately gave me a superior crash course on nonprofit management in coming years. By that second year or so, we started to grow from the 12 boys. By 2009, we had our tax-exempt status and received our first major grant, from the Black United Fund of Illinois, the largest African American self-help organization in Illinois, who I worked for at the time. We were granted $8,000, which for me was a huge amount of money. First year I had spent about $1,500, majority out of pocket, for umpire fees, traveling, giving the kids something to eat and equipment. From there we expanded to five teams and created our own league. We folded in our operation with Rosemoor Little League and have been part of that ever since. BD: Lost Boyz has become about much more than baseball. How did that evolution take place? LS: What I also discovered in those first two years, getting the kids to function is a difficult and daunting task, depending on the demographic I’m working with. It’s not necessarily race, it’s economic data and academic information and what schools are the kids going to. How much money are their parents making, where do they live, what are their lives like? The average Little League kid comes from a stable, middle-class home. Kids that come from lower-income, less-stable homes, they’re usually not the best candidates for baseball because of all the support that has to come behind it from parents. Whether the money, uniforms, equipment, transporting them to practices and games. There has to be support for them to play. So I started delving a little deeper and noticing some kids were having academic issues, some kids social issues at home or with other kids. That’s when my focus became working with kids who are experiencing these different issues that are throwing them off. That’s where the reflection of my own life started kicking in. The things I lacked, the troubles I got off into, were the very things I was trying to prevent with these kids. So I started thinking deeper than baseball and augmenting with other components. I started fiddling along with a theory in my head, a connection of causation, so I was hitting on this existing social science theory called sport-based youth development, using and leveraging the power of sport to create individual and social change. I knew that relationships were important, that mutually beneficial relationships place kids on a better trajectory in life. With organized baseball, we took care of the social aspect from the sport. Then we started looking at academics, and added in academic enrichment, tutoring and homework help, and checking grades and tying that into the program and starting to track outcomes and figuring out where things relate. Then we started looking at civic engagement and cultural awareness, and getting kids involved in things that impact their lives on a daily basis. With so much segregation in Chicago, another staple was exposing them to other cultures so they are not so surprised when they see things but have a respect for other cultures. And visiting neighborhoods outside the South Side. BD: The postsecondary and workforce component seems a natural next step after the kids participate in Little League. LS: I’d ask kids, why weren’t you at practice? They couldn’t be at practice because my mom was at work and they didn’t have any bus fare. It’s like, wow—it eventually kept pointing back to money. Teenagers need pocket money. I have three teenagers now, and they constantly need money. So I thought this is the issue that drives black males into the street, it’s because of this desire for some money. And if the workforce isn’t open to them, then what can they do to have some money. I created SYL, Successful Youth Leaders, which became a continuum of service. It was part of the same program, but instead of playing we substituted being part of a team and earning a wage and creating jobs around the industry. We created four tracks: junior umpires, statistician, grounds crew and sports journalism. These could all be lucrative careers—there is a lot of money to be made there. BD: Could you ever have foreseen being in this position all those years ago in Missouri? LS: One of my favorite statements is if you want to make god laugh, tell him your plans. Starting Lost Boyz was really no surprise, that is who I am and have been all my life. Some way, somehow I would have arrived at this point.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The only social impact Q&A on the web

AboutThe idea behind The Fact Sheet is to document interesting conversations with super-interesting people. Archives

December 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed