|

What is it about stories, anyway?

Here's what author Frank Rose wrote in 2013: Just as the brain detects patterns in the visual forms of nature—a a face, a figure, a flower—and in sound, so too it detects patterns in information. Stories are recognizable patterns, and in those patterns we find meaning. We use stories to make sense of our world and to share that understanding with others. They are the signal within the noise. I've been working on a new film, another one about birds. This time, though, there isn't a species as charismatic as the Piping Plover. It's going to take a different approach to make this story as compelling. It's going to take a different way of tapping into those recognizable patterns. My current thinking is that I'll feature a few powerful stories from the people tracking the sandpipers, while doing my best to get close-ups of the birds to show their behavior and personalities. These species may sometimes come off as nondescript, but combined with the visual forms above and a few human patterns there will be added meaning and something that truly stands out. One could shout from the rooftops about something interesting, but without a story there's often nothing substantial there, little that will resonate with the viewer. Little that's memorable. I hearken back to a long-ago job at a large nonprofit organization. We could write at length about why our mission was important, and about our programs and services, as most organizations do, but we struggled to create memorable content that told a story. It was a missed opportunity and often left our audiences wanting more. The neat thing is, with storytelling, one can be creative and entertaining, too. It means we can have a little fun, and in this line of work there is indeed quite a bit of self-seriousness. Anthropologists love to state that storytelling is central to human existence, common to every known culture. Storytelling's an art as old as the first cave paintings and a skill set that every organization should possess. And here's why: Because a distinctive narrative can make most any subject matter meaningful to everyone, even a few sandpipers.

0 Comments

Something that's worked lately for nonprofit clients are targeted posts to LinkedIn and Twitter. That’s what sparked the thought for this post. Here are four principles I’ve identified—and often turn to—in more than 10 years of professional experience in social media.

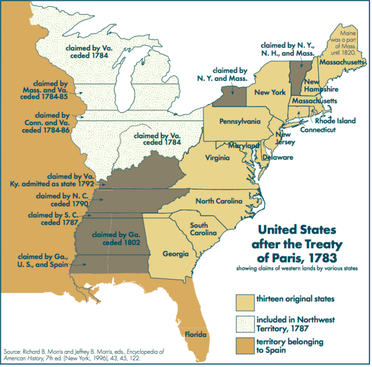

An adequate frequency of posts When I started Turnstone Strategies four years ago, my advice to clients was to provide a high frequency of posts. It seemed that was the way to remain visible and generate more interest in products and services. I’ve adjusted this approach recently, mostly because organizations don’t have the capacity to post frequently. Organizations may have one or two Communications staff at most, many have none. and Communications is rolled into someone else’s duties. While I might be able to help as a consultant, after I’m gone any momentum is at risk of being lost. Now I recommend an adequate number of posts, that is, enough to show that the organization is still in business while occasionally engaging with partners and driving traffic back to the website. Rightsizing the frequency of posts depends on the capacity of the team and the importance of social media to the overall strategy. Algorithms and blues Facebook and LinkedIn have algorithms that favor photos, interactivity, and frequent posting. Instagram and Twitter are a little different. In some ways though, they are easier to crack when it comes to increasing engagement. It’s best not to try to shoehorn a strategy onto a platform with a less favorable algorithm, though. Facebook is a great example of this. I manage three pages with a combined following of about 4,000. Many photo and link posts receive only a handful of reactions, however. Videos are even worse. I can create a stellar video and get even fewer engagements (Facebook really doesn’t like something about video). So I’ve decided not to try to beat the algorithm, as it would consume inordinate amounts of time and energy—time that most of us simply don’t have. I’ll be candid in sharing that I shelved Facebook for one of my clients because there was little to no return on the time investment it took to keep it up. LinkedIn can be a missing, well, link I remember starting the LinkedIn page for a major Chicago nonprofit years ago. The thought was that it was secondary to Facebook and Twitter (at that time there was no Instagram). Only the most astute corporate networkers were on LinkedIn. It was a small group and when it came to nonprofits it was really tiny. That’s changed through the years as most any professional in most any industry has a basic LinkedIn profile. LinkedIn now encompasses 830 million members in more than 200 countries and territories. In working with smaller organizations, I realize how vital it is to be active on LinkedIn, attracting potential employees and staying top-of-mind with peer organizations and experts in the field. A recent client post was evidence of this as it went viral and we saw a 50% increase in followers in just under three weeks. And this was an organization that hadn’t been posting often until this spring. Organizations are people, too On Twitter, you can be Joe Biden or you can be Donald Trump. Most organizations should fall somewhere in between. President Biden is laconic on Twitter, to the point of being too dry. Former President Trump, well, he is former President Trump. When he was on Twitter it was a daily communications crisis and occasional constitutional crisis. That’s something to avoid. Organizations should personalize their feeds, have some fun, engage with followers, and actively like and retweet posts. Be part of the local Twitter community. This can lead to real-life partnerships that bring new people into the fold and further the mission. Unfortunately, many Twitter feeds end up as a compilation of links and corporate-speak while going dormant for long periods. Bob Dolgan is the founder of Turnstone Strategies. By Kara Morrison On this day in 1795, the Treaty of Greenville was signed almost a year after General Anthony Wayne declared U.S. victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The treaty marked the formal end of the Northwest Indian War. After the Revolutionary War, the U.S. government began laying out more detailed plans for defining and selling land, especially in the newly acquired Northwest Territory. While the British had treaties with many of the indigenous groups in the Northwest Territory, once they ceded the land to the U.S. in the Treaty of Paris, the U.S. government did not feel bound to these agreements. As U.S. settlers pushed westward, the government increasingly called for the removal of indigenous communities already inhabiting the Northwest Territory. Map courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society from the Encyclopedia of American History, 7th ed. by Richard B. Morris and Jeffrey B. Morris. The U.S. government continued applying pressure on indigenous leaders to cede their land, often using military force. As indigenous groups formed a British-backed confederation, known as the Western Confederacy, and became more actively and effectively resistant to U.S. military pressure and violence, the U.S responded with more force and conflict soon developed into what became the Northwest Indian War. While the Western Confederacy saw many victories for the first half of the war and negotiating attempts repeatedly took place both between indigenous leaders and between the Western Confederacy and the U.S., the last years of the war brought more forceful and well-trained U.S. troops and more defeats for the Western Confederacy. After the ultimate defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, negotiations began between General Anthony Wayne and Western Confederacy leaders. The Treaty of Greenville resulted in indigenous leaders ceding much of their land to the U.S. in return for annuity payments that ultimately also gave the U.S. a significant amount of control over indigenous nations. For many indigenous groups including the Wyandots, Delawares, Shawanees, Ottawas, Chippewas, Pattawatimas, Miamis, Eel Rivers, Weas, Kickapoos, Piankeshaws, and Kaskaskias, the Treaty of Greenville signified a major loss of their homeland and way of life. Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public.

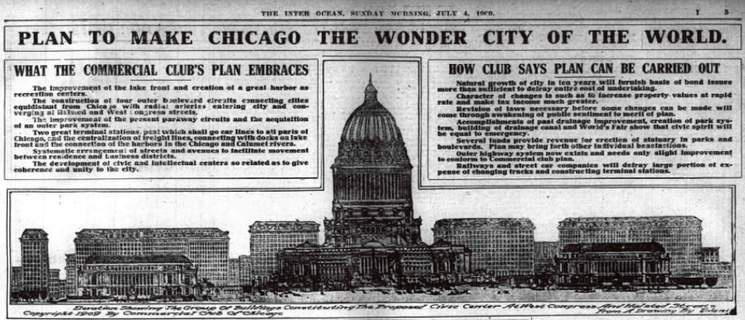

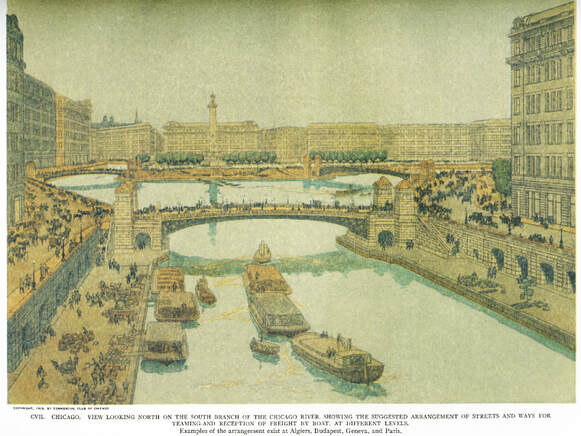

By Kara Morrison “Plan to Make Chicago the Wonder City of the World,” Inter Ocean, July 4, 1909. Courtesy of Newspapers.com On this day in 1909, The Plan of Chicago, by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, was presented to the city of Chicago. Often referred to as the “Burnham Plan of Chicago,” the plan proposed a series of projects intended to improve the city’s layout, commerce, as well as the daily life of the people of Chicago. At the time the plan was created, Chicago was one of the fastest growing cities in the world and many recognized the need for a plan for a city growing at such a rapid rate. In 1906, a group of businessmen appointed renowned architect Daniel Burnham to create such plans for the city. This group of businessmen soon formed the Commercial Club of Chicago and published the Burnham Plan of Chicago just a few years later. Burnham hired another architect and planner, Edward H. Bennett, to assist him in researching and developing the project. They studied various cities throughout the world and observed how the infrastructure of similarly growing cities impacted their economies and communities. The plan as presented to the Chicago City council in 1909 included numerous illustrations and six central elements to address in order to improve the city of Chicago. Select parts of the plans were implemented in the next few years, such as the widening of Chicago streets and the area reserved for a public park on Chicago’s lakeshore. While not all of the Burnham Plan was implemented it had a major impact on Chicago and the future of urban planning and remains a reference for city planners today. An illustration from the Plan of Chicago, courtesy of the Chicago Public Library, Plan of Chicago Special Collections Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public.

We love it when a plan comes together!

On April 7, the Chicago Park District announced that 3.1 acres would be added to the Montrose Beach Dunes Natural Area. This outcome is the result of a coordinated effort that included: -A documentary film on an endangered species -The proclamation of Piping Plover Day by Gov. Pritzker -The support of Ald. Cappleman -Dozens of emails as well as public comment -An op-ed and letter in the Sun-Times -Interface with local media throughout -Direct outreach to Park District leadership Cheers to the expansion of Chicago's lakefront natural areas! By Kara Morrison Former Vice President Al Gore and Hazel Johnson meeting at the White House, undated. Courtesy of Chicago Public Library People for Community Recovery Archives, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature On this day in 1935, Hazel M. Johnson, founder of People for Community Recovery, was born. After first moving to Chicago in the 1950s, Johnson and her husband moved to Altgeld Gardens Homes, a public housing project originally built to house African American veterans on Chicago’s south side, in 1962. By the time Johnson’s family moved there, Altgeld Gardens Homes had been taken over by Chicago Housing authority and housed almost 10,000 mostly low-income residents. In the early 1970s, after seeing a television program connecting cancer to certain environments, Johnson began suspecting her husband’s death from cancer just a few years earlier may also be linked to their community’s environment. She began investigating and found that not only was there a higher rate of cancer among her neighbors, but also that there were many children in the area, including her own, suffering from various skin and respiratory issues. She soon learned that Altgeld Gardens was not only teeming with toxic emissions from surrounding landfills, toxic waste dumps, and industrial factories, but that Altgeld Gardens Homes had actually been built on a landfill. Johnson educated and organized her neighbors, founding People for Community Recovery. They collected data and health surveys showing evidence that their low-income, minority community suffered from a disproportionate amount of surrounding pollution. Johnson and People for Community Recovery confronted many of the companies polluting their community, even confronting the Chicago Housing Agency itself, and later working with them to carry out projects that could help improve their living conditions. Johnson turned her grassroots movement into a larger effort to fight against environmental racism in communities of color across the U.S. Later, Johnson at time worked with EPA and even worked towards urging President Clinton to sign the Environmental Justice Executive Order. You can find more information about environmental racism and its more recent impacts here. Hazel M. Johnson at the presidential signing of Executive Order 12898. Courtesy of Cheryl Johnson, “Mama Johnson: A Visionary Who Inspired Her Country,” The EPA Blog, February 19, 2014. Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public. Sources cites: Chicago Public Library, The EPA Blog

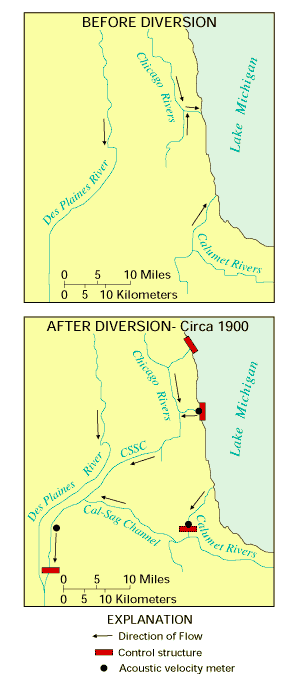

By Kara Morrison On this day in 1900, the Chicago Drainage Canal officially opened, connecting the Chicago River to the Des Plaines River and reversing the direction of the Main Stem and South Branch of the Chicago River, making it flow away from Lake Michigan. Prior to this, the Chicago River had flowed into Lake Michigan. Unfortunately, the water from the Chicago River flowed rather slowly into Lake Michigan and, as the population of Chicago increased, the river became increasingly contaminated with sewage and pollution. This sewage ran right into Lake Michigan, polluting the area located around the mouth of the Chicago River, where Chicago also happened to get their water supply. After an 1885 storm washed contaminants much farther throughout Lake Michigan, people became heavily concerned this would cause an epidemic. In 1887 it was decided to build the Chicago Drainage Canal in order to avoid these public health concerns, as well as to supplement the shallow and polluted Illinois and Michigan Canal. Engineer Isham Randolph planned to cut through the 12 miles that separated the Great Lakes drainage system from the Mississippi drainage system, and the Sanitary District of Chicago was created to carry out these plans. Although many obstacles were met during the creation of the canal, such as a large 1893 strike, the canal was completed in 1900. The opening of the Chicago Drainage Canal was announced January 2, 1900, and the reversal of the Chicago River is still considered a major feat in civil engineering. Waterways in the Chicago area before and after the Lake Michigan diversion. Courtesy of USGS. February 18, 2014. Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public. Sources cited: American Society of Civil Engineers, U.S. Geological Survey

By Kara Morrison On this day in 1916, Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, held hearings in Chicago to gauge public opinion on a “Sand Dunes National Park.” Over 400 people attended, with many speaking in favor of the park, and without a single person speaking in opposition. While the movement to turn the dunes into a national park largely stalled for another 40 years, the work to preserve the dunes continued. After a 10-year petition, the Indiana Dunes State Park opened in 1926. Later, in 1952, Dorothy Buell met with a group of women to discuss a campaign to preserve the dunes and establish an Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, ultimately founding the Save the Dunes Council. Around the same time, many politicians and businessmen were also trying to obtain funds to construct a “Port of Indiana” and link the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. Buell and other council members began a fundraising campaign to save the dunes and were eventually able to purchase a 56-acre area of what is now Cowles Bog. Dorothy Buell, courtesy of NPS Image Collection, “History of Indiana Dunes National Park,” National Park Service, March 19, 2020.In addition to the Save the Dunes Council, Illinois Senator Paul H. Douglas, was crucial in establishing the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. He led public and congressional efforts to preserve the dunes. When the Kennedy Compromise was introduced, a program linking the need for both a national lakeshore and ports for industry, Douglas made sure the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore would be included and preserved. Thanks to these collective efforts, the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was authorized by Congress on November 5, 1966, and on February 15, 2019, it was renamed Indiana Dunes National Park, becoming Indiana’s first national park. Senator Paul H. Douglas speaking. Courtesy of the Digital Public Library of America Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public. Sources cited: National Park Service, Save the Dunes, Digital Public Library of America, University of Illinois at Chicago

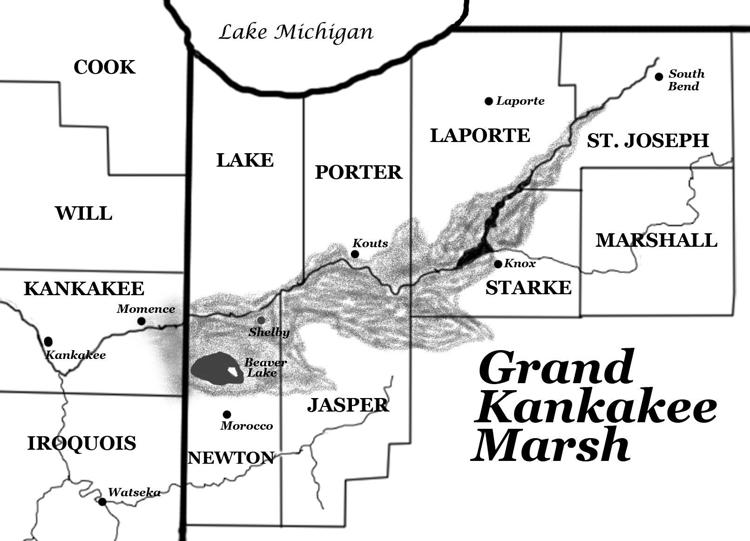

By Kara Morrison On this day in 1925, the Bremen Enquirer of Bremen, Ind., announced the completion of the Kankakee River Ditch, marking the almost complete destruction of the Grand Kankakee Marsh. A century earlier, the Grand Kankakee Marsh was the largest inland wetland in the U.S. and was home to a vast array of animal and plant species. Efforts to drain the Kankakee Marsh began just before the 1850s, when small channels and ditches began being dug into the wetland. With the introduction of the Swamp Land Act of 1850 and steam-powered dredge boats, efforts to reduce the Kankakee River and drain the marsh picked up rapidly. Steam-powered dredges allowed for deeper ditches and bigger levees. These massive dredge-dug channels resulted in the Kankakee River being reduced to less than half of its original length. Despite all this progress, the Grand Kankakee Marsh was still reluctant to drain, thanks to a natural limestone dam. In 1893, the state of Indiana approved funding to begin cutting a massive channel through the limestone, eventually having the desired effect of allowing much more of the marsh to drain at a much quicker rate. Over the next 30 years, the river continued to be cut down to only 90 miles and the marsh continued to be drained until it was almost completely gone. One of the steam dredges that channelized the Kankakee River in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “A Look Back: Kankakee Marsh was largest inland wetlands in the U.S.,” South Bend Tribune, April 10, 2018. Courtesy of The History Museum. Today there are efforts, such as Friends of the Kankakee and their Kankakee National Wildlife Refuge and Conservation Area (KNWR&CA) to protect and restore the Kankakee River Basin, and help save an array of threatened species in the area. Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public. Sources cited: South Bend Tribune, The Daily Journal, The Bremen Enquirer

MEARS, Mich. -- The weekend of October 10-11 brought us to western Michigan for filming on piping plover breeding grounds, specifically the locations where Monty and Rose hatched in 2017. We gained enormous insight into the life cycle of Great Lakes piping plovers while there, but it was the towering sand dunes of Silver Lake State Park that left the biggest impression on us. These dunes are vast and a sort of mini-Sleeping Bear Dunes, about halfway south along the mitten, between Ludington and Muskegon. Sarina Haasken of the Great Lakes Piping Plover Recovery Project kindly joined us and showed us around the majestic landscape. We trekked to a high point on the dunes, between Lake Michigan and Silver Lake itself, which is ringed by open sands and forested inclines. While we were there, we were astonished to find two piping plover eggs from the previous nesting season. The eggs were from an early clutch belonging to YOGi and BYL, and dated to June, according to Sarina, who carefully recovered them. They were found in an expanse surrounded by acres and acres of sand in every direction. From there, we traveled to Muskegon State Park, which was a true pleasure as well. Plover monitors Carol Cooper and Heather Sellon showed us where piping plovers have nested near the beach house there. For us, this was a more conventional setting for piping plover nesting, as it had some resemblance to Montrose Beach in Chicago.

In addition to these sites, we visited Ludington State Park and met local birders Dave Dister and Joe Moloney, who gave us some of the history of piping plovers in Mason County. It was wonderful to meet birders on the other side of Lake Michigan and share the story of Monty and Rose with them. We are thrilled with the video we captured on this trip and look forward to sharing it when the time comes to complete "Monty and Rose II." --Bob Dolgan |

The blog is a space for stories of the natural world and the occasional post about communications and strategy.

Archives

September 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed