|

By Georgie Lellman On March 26, as the pandemic was beginning to have serious and far-reaching impacts within the United States, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot closed the Lake Michigan lakefront for all recreational activities. The closure meant that Montrose Point, a spot that attracts crowds of birdwatchers--and birds--would have nearly zero observations in April and May, a far cry from the 237 bird species observed in 2019. “It’s a perfect place for migrants flying over or along the lake to land, rest, and fuel up for their next flight,” said birdwatcher Isoo O’Brien. Montrose attracts birdwatchers because of its convenient location, diversity of habitats, and eye-level bird sightings. However, because of the closure, eBird data show how birders went elsewhere. Graceland Cemetery, a shaded cemetery and arboretum just blocks from Montrose, experienced one of the biggest increases in observations, even as it has slowly been gaining in popularity among birders in recent years. Graceland recorded more bird species in 2020 spring migration (153 to be exact) than had been recorded in the last 10 years combined. Additionally, Graceland saw 30 distinct warbler species this past spring, while recording only 28 species during spring migration over the last decade. Weekly maximum sightings during spring migration for several migratory species included: 35 Hermit Thrushes, 20 Rose-breasted Grosbeaks and 20 Baltimore Orioles, compared to previous records of 17, 15 and nine observations of these species, respectively. “Graceland was the alternative destination for people seeking the convenience of a nearby migrant trap,” explains O’Brien, a high school senior who is trying to break Cook County’s big year record by observing 281 distinct species.

O’Brien spent time birdwatching at Northwestern University, Jackson Park and southern Cook County. But another site, Washington Park on the South Side, also experienced dramatic increases in the number of bird species observed, reaching 193 this season, an increase of over 65 species from its previous maximum of 125 species during spring migration in 2017. The number of warbler species observed at Washington Park also grew, with 35 species recorded this season compared to 30 warbler species recorded over the last decade. As bird observations of spring migration were heavily impacted in the Chicago area by the Covid-19 pandemic, it will be interesting to see if Graceland Cemetery and Washington Park continue to be popular birdwatching destinations through fall migration, with Montrose Point partially open for recreational activity. Montrose Point and its wildlife had a quiet and relaxed spring migration. Birdwatchers did not relent, but turned their attention elsewhere, discovering new sites, like Graceland, and bolstering the eBird data available for these less popular destinations. Even with discoveries of new birding sites, O’Brien, who prefers Montrose Point, expects typical patterns to return in the future. “I imagine next spring [Graceland Cemetery] won't be as popular as it was this year,” he says. Georgie Lellman is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and an intern for Turnstone Strategies. She is interested in environmental law and passionate about wildlife issues. Contact Georgie at [email protected].

1 Comment

By Kara Morrison

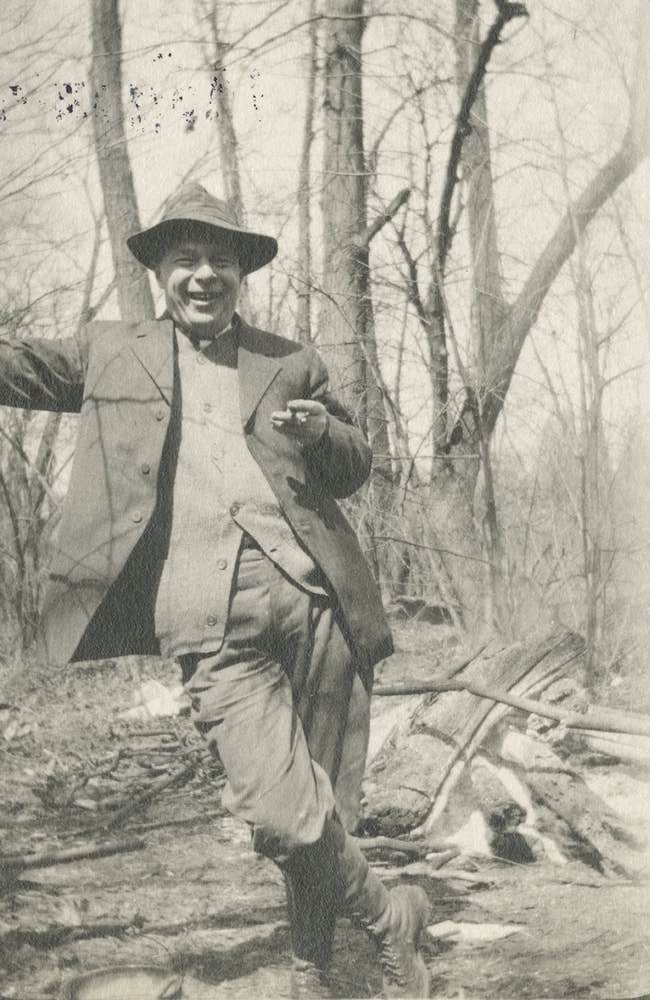

Henry Chandler Cowles passed away on this date in 1939 at 70 years of age. Cowles was an American botanist and early ecologist who was fundamental in founding the Ecological Society of America and his work helped lead to the creation of Indiana Dunes National Park. Cowles’ research emphasized and investigated the inherently changing nature of plants and their natural environment. More importantly, unlike many botanists and ecologists at the time, he was less focused on his own research and more focused on the work of his students. Cowles often took his University of Chicago students to areas around the Great Lakes and even as far as the West Coast. Although he traveled far and wide to study ecology, his greatest influence was his own local area. He first visited the Indiana Dunes in 1896, and continued to travel to observe the dunes throughout various seasons over the years, eventually developing concepts around plant succession and climax formation that would become crucial to ecological studies. Cowles Bog, a part of what is now Indiana Dunes National Park, is named in honor of Cowles and his work that brought such widespread attention to the Indiana Dunes. Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public. Sources cited: National Geographic Resource Library, University of Chicago Centennial Catalogues

Todd Pover is a Senior Wildlife Biologist at the Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey and manages populations of beach nesting birds including piping plovers, least terns, and black skimmers. We had the opportunity to speak with him about the importance of piping plover monitoring and the challenges these endangered birds face. Edited for length and clarity.

By Georgie Lellman Why is monitoring piping plovers so important? Well, first of all piping plovers are federally listed and in New Jersey, where I do most of my breeding field work, they’re state listed. So, in order to be able to track the species you have to have really solid and pretty intensive monitoring. If you are not doing really close monitoring you can’t figure out the causes for nest or brood loss. Because our goal is to recover the species, in order to better manage them we have to know those causes. Piping plovers are in a sandy environment, so when you get a windy day or a rainy day the evidence of predators can disappear quickly. So you really need to be there on a daily basis to be able to determine some of these issues. What ecological role do piping plovers play? This is a question I hear quite frequently over a couple of decades of work. I think a lot of people focus on species that when you pull them out of the ecosystem the whole system collapses. That’s probably not the case for piping plovers. We don’t know the intricate ecological web of how these species fit together, but I think more importantly piping plovers sort of represent whether you have a healthy functioning ecosystem, because those that are severely altered and changed less frequently have piping plovers. In New Jersey we are a highly developed and recreated beach so we have these protected natural areas and that is where our highest concentration of plovers are. How did the 2020 monitoring season go? This year was a particular challenge because of COVID and the pandemic. We did find, because nature was one of the things that people were able to get out into, our beaches were actually busier than normal in the spring, which is a critical time when birds are trying to set up. That could have impacted them in a negative way. Generally speaking, birds did pretty well in New Jersey this year. I'm responsible for Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge and that site has 39 pairs of piping plovers this season and is one of the most important spots in New Jersey and happened to do very well. Of the 39 pairs, they fledged about 1.7 chicks per pair, which is above the Atlantic Coast Recovery level of 1.5. In New Jersey this is our Achilles heel. We have historically had a lot of difficulty fledging young. We do pretty well with our hatch rate, but fledging is where we come up short. So for us to have a high level like that was a good outcome for us. Why do you generally have low success fledging chicks? Well, there are a lot of factors, so it's hard to pinpoint the exact one. It could be a bad weather year or something along those lines, but generally speaking New Jersey is really highly developed. In fact, beaches are so highly used that we could put a fence around the areas or the nest and keep people out but once the piping plovers hatch they'll leave those areas to forage at the water's edge. Often those areas at public beaches can’t be protected in the same intensive way. That impacts their survival. Because the breeding ground is so close to the beach area, there are restaurants and houses and it's close to sources of food for predators, so we have a higher concentration of predators around the beach. It's a combination of those things. Lastly, the factor we understand least is highly engineered beachfill, which we think probably impacts the foraging suitability. More and more we’re understanding that access to really good undisturbed, but also highly productive foraging areas, is really important for survival for those chicks. How have the numbers of piping plover pairs changed over the time you have been monitoring them in New Jersey? Well for me, yeah. This is 25 years plus for me, so I’ve seen a lot of fluctuation. From a high of about 140 pairs to a low of 90-some pairs, percentage wise that's a big change. Unfortunately, we’re sort of at the lower edge of that at the moment and we’re struggling to get back. We have years where we have better numbers, but we’re a little bit stuck on the wall at the moment. For the last 5 years we have seen higher fledge rates than we probably have ever seen over the same period so we’re hoping that’s going to push us to the next level. A huge caveat though is once the birds leave you’re facing the same issues. What happens is during migration and wintering the birds spend more time away from the breeding grounds than on it and their survival during migration or over the winter impacts our populations. Hurricanes that have hit Florida and the Bahamas, where you have wintering plovers, have really bad impacts potentially on survival. So, we can have a really good year, but have a lot of mortality over the winter due to hurricanes or other factors. What are some of the biggest obstacles to the success and survival of piping plovers in New Jersey? How do you overcome these obstacles? Well, the habitat really matters and I think it all starts with really good habitat, but we’ve also seen situations where birds can do okay in slightly less suitable habitat. Unfortunately it's not a magic button answer. It really is a case where we need everything for them to do well. So you need the habitat, really strong protection, and management of everything from the people component to the predators. And then I think outreach is really important. I think we’ve seen that, in a lot of cases, people don’t really want to disturb or negatively impact birds, but they just aren’t aware that their activity is going [to have that impact]. So, trying to have someone at the sites, the public ones at least, is a really important part of it as well. Communication, outreach, and management all have to fit together for a successful piping plover program. Georgie Lellman is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and an intern for Turnstone Strategies. She is interested in environmental law and passionate about wildlife issues. |

The blog is a space for stories of the natural world and the occasional post about communications and strategy.

Archives

September 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed