|

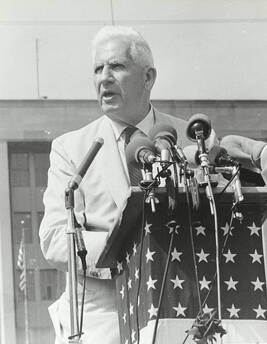

By Kara Morrison On this day in 1916, Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, held hearings in Chicago to gauge public opinion on a “Sand Dunes National Park.” Over 400 people attended, with many speaking in favor of the park, and without a single person speaking in opposition. While the movement to turn the dunes into a national park largely stalled for another 40 years, the work to preserve the dunes continued. After a 10-year petition, the Indiana Dunes State Park opened in 1926. Later, in 1952, Dorothy Buell met with a group of women to discuss a campaign to preserve the dunes and establish an Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, ultimately founding the Save the Dunes Council. Around the same time, many politicians and businessmen were also trying to obtain funds to construct a “Port of Indiana” and link the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. Buell and other council members began a fundraising campaign to save the dunes and were eventually able to purchase a 56-acre area of what is now Cowles Bog. Dorothy Buell, courtesy of NPS Image Collection, “History of Indiana Dunes National Park,” National Park Service, March 19, 2020.In addition to the Save the Dunes Council, Illinois Senator Paul H. Douglas, was crucial in establishing the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. He led public and congressional efforts to preserve the dunes. When the Kennedy Compromise was introduced, a program linking the need for both a national lakeshore and ports for industry, Douglas made sure the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore would be included and preserved. Thanks to these collective efforts, the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was authorized by Congress on November 5, 1966, and on February 15, 2019, it was renamed Indiana Dunes National Park, becoming Indiana’s first national park. Senator Paul H. Douglas speaking. Courtesy of the Digital Public Library of America Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public. Sources cited: National Park Service, Save the Dunes, Digital Public Library of America, University of Illinois at Chicago

1 Comment

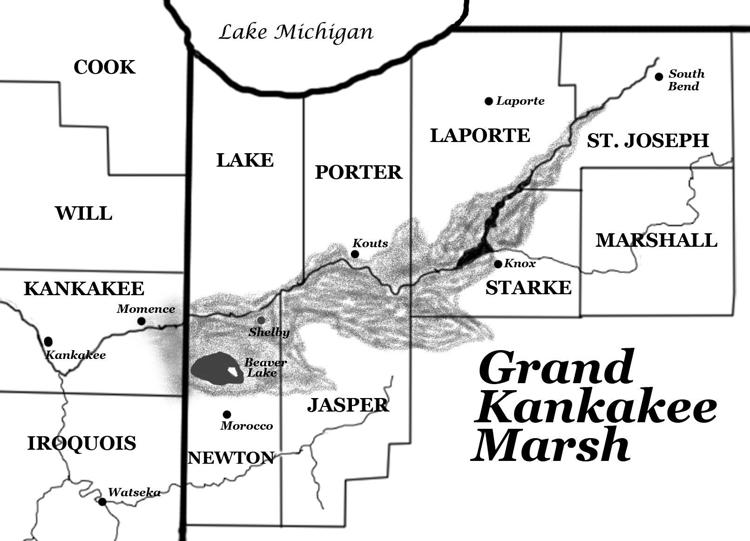

By Kara Morrison On this day in 1925, the Bremen Enquirer of Bremen, Ind., announced the completion of the Kankakee River Ditch, marking the almost complete destruction of the Grand Kankakee Marsh. A century earlier, the Grand Kankakee Marsh was the largest inland wetland in the U.S. and was home to a vast array of animal and plant species. Efforts to drain the Kankakee Marsh began just before the 1850s, when small channels and ditches began being dug into the wetland. With the introduction of the Swamp Land Act of 1850 and steam-powered dredge boats, efforts to reduce the Kankakee River and drain the marsh picked up rapidly. Steam-powered dredges allowed for deeper ditches and bigger levees. These massive dredge-dug channels resulted in the Kankakee River being reduced to less than half of its original length. Despite all this progress, the Grand Kankakee Marsh was still reluctant to drain, thanks to a natural limestone dam. In 1893, the state of Indiana approved funding to begin cutting a massive channel through the limestone, eventually having the desired effect of allowing much more of the marsh to drain at a much quicker rate. Over the next 30 years, the river continued to be cut down to only 90 miles and the marsh continued to be drained until it was almost completely gone. One of the steam dredges that channelized the Kankakee River in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “A Look Back: Kankakee Marsh was largest inland wetlands in the U.S.,” South Bend Tribune, April 10, 2018. Courtesy of The History Museum. Today there are efforts, such as Friends of the Kankakee and their Kankakee National Wildlife Refuge and Conservation Area (KNWR&CA) to protect and restore the Kankakee River Basin, and help save an array of threatened species in the area. Kara Morrison is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and a contributor to the Turnstone Strategies blog. She is passionate about making historical and educational information accessible to the public. Sources cited: South Bend Tribune, The Daily Journal, The Bremen Enquirer

MEARS, Mich. -- The weekend of October 10-11 brought us to western Michigan for filming on piping plover breeding grounds, specifically the locations where Monty and Rose hatched in 2017. We gained enormous insight into the life cycle of Great Lakes piping plovers while there, but it was the towering sand dunes of Silver Lake State Park that left the biggest impression on us. These dunes are vast and a sort of mini-Sleeping Bear Dunes, about halfway south along the mitten, between Ludington and Muskegon. Sarina Haasken of the Great Lakes Piping Plover Recovery Project kindly joined us and showed us around the majestic landscape. We trekked to a high point on the dunes, between Lake Michigan and Silver Lake itself, which is ringed by open sands and forested inclines. While we were there, we were astonished to find two piping plover eggs from the previous nesting season. The eggs were from an early clutch belonging to YOGi and BYL, and dated to June, according to Sarina, who carefully recovered them. They were found in an expanse surrounded by acres and acres of sand in every direction. From there, we traveled to Muskegon State Park, which was a true pleasure as well. Plover monitors Carol Cooper and Heather Sellon showed us where piping plovers have nested near the beach house there. For us, this was a more conventional setting for piping plover nesting, as it had some resemblance to Montrose Beach in Chicago.

In addition to these sites, we visited Ludington State Park and met local birders Dave Dister and Joe Moloney, who gave us some of the history of piping plovers in Mason County. It was wonderful to meet birders on the other side of Lake Michigan and share the story of Monty and Rose with them. We are thrilled with the video we captured on this trip and look forward to sharing it when the time comes to complete "Monty and Rose II." --Bob Dolgan By Georgie Lellman

Despite the odds, an innovative new bill hailed as the greatest piece of land conservation legislation in decades became law this summer. The bipartisan Great American Outdoors Act, sponsored by Republican Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado, received support from 59 senators and passed on June 17. It was a rare moment of bipartisanship in today’s political climate, making the August 4 signing of the law even more monumental. But what exactly does the Great American Outdoors Act actually accomplish? The act has two primary goals. Its long-term objective is to provide permanent funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), which funds public lands. The LWCF was created in 1965 by President Lyndon B. Johnson, but has only been funded by Congress in its full amount of $900 million per year twice since its creation. In the past, the funds have instead been used for unrelated projects. The Great American Outdoors Act ensures that the funds, from this point forward will be allocated annually to the LWCF to conserve and protect public lands across the nation. These new permanent funds will increase funding for the U.S. Forest Service by $285 million annually, and by $95 million annually for both the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Together, these organizations encompass over 588 million acres of land, that's approximately five times the size of the entire state of California. And, while public lands should see extraordinary benefits from the Great American Outdoors Act, it will also provide advantages for communities across the nation. According to economists, every dollar invested by the Land and Water Conservation Fund generates a $4 return in their communities, boosting the economies in localities closely connected with public lands. The secondary aim of the legislation stipulates that $9.5 billion be set aside over the course of the next five years in the Public Lands Restoration Legacy Fund to address previously neglected maintenance issues that affect many national and state parks. According to the American Hiking Society, “There is a nearly $12 billion backlog of maintenance projects across our public lands. When annual maintenance needs go unaddressed, long-term problems arise, seriously hampering the public’s access to outdoor recreation.” This backlog has been created by an increase in visitors to public lands by over 50% since 1980 and a parks budget that has remained relatively unchanged. Of the money placed in the Public Lands Restoration Legacy Fund, $6.5 billion is specifically intended to be used across the national park system, while the remaining funds will aid wildlife refuges, forests, and other public lands. Interestingly, the $1.9 billion provided annually will be generated from oil and gas drilling revenues on the Outer Continental Shelf, submerged land along the east and west coasts of the U.S. as well as the Gulf of Mexico. This allows the American people to see a return for energy development and resources taken from their public land. The passing of the Great American Outdoors Act is a sign of hope that the challenges that the American people face in pursuing outdoor recreation opportunities at national and state parks will now be addressed through this influx of funds, which have been absent for decades. The Great American Outdoors Act deserves praise as it will help to ensure the continued beauty of our natural spaces and that public lands remain accessible for generations to come. Georgie Lellman is a recent graduate of Kenyon College and an intern for Turnstone Strategies. She is interested in environmental law and passionate about wildlife issues. Sources: The Wilderness Society. 2020. “Land and Water Conservation Fund fully funded after decades of uncertainty." Harsha, Dan. 2020. “The biggest land conservation legislation in a generation”. The Harvard Gazette. Leasca, Stacey. 2020. “The Great American Outdoors Act Could Give Billions of Dollars to National Parks — Here’s What You Need to Know”. Travel + Leisure. |

The blog is a space for stories of the natural world and the occasional post about communications and strategy.

Archives

September 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed